Introduction

Welcome to “Chinese Martial Arts in the News.” This is a semi-regular feature here at Kung Fu Tea in which we review media stories that mention or affect the traditional fighting arts. In addition to discussing important events, this column also considers how the Asian hand combat systems are portrayed in the mainstream media.

While we try to summarize the major stories over the last month, there is always a chance that we have missed something. If you are aware of an important news event relating to the TCMA, drop a link in the comments section below. If you know of a developing story that should be covered in the future feel free to send me an email.

Its been a while since our last update so there is a lot to be covered in today’s post. Let’s get to the news!

News from All Over

Our first story comes from the (digital) pages of the South China Morning Post. It recently carried a short article looking at Karate’s Chinese origins. This discussion comes on the heels of Karate’s inclusion in the upcoming Tokyo Olympic games, while Wushu once again finds itself on the outside looking in. However this particular piece focuses instead on the academic research of a Chinese scholar named Lu Jiangwei (from Fujian) who recently completed a doctoral dissertation looking at the origins of “Karate culture” at the Okinawan Prefectural University of Arts. This is an interesting project as it is clearly encouraging a fair bit of international cooperation among researchers. At some point I will need to see if I can learn more about Lu’s research methods and findings.

Perhaps the most famous master of the traditional Chinese martial arts to make the news this week was the noted Hung Gar practitioner Wong Fei Hung. While he ended his life as a recluse, Wong is perhaps the best known Kung Fu personality of his generation because of the many newspaper stories, novels, radio programs and movies that have embroidered his legacy. A short note in The Star reports that Wong’s real life disciples and students were unsuccessful in their recent attempts to locate his historic grave. Apparently the cemetery that he was laid to rest in was demolished to make room for a new high rise development. While only a short note, this story reinforces the inherent challenges involved in preserving and understanding the physical and architectural history of the Chinese martial arts in a constantly shifting landscape.

Speaking of change, ECNS ran a story on the efforts of mixed martial artists (and the promoters behind the ONE Championship) to establish a foothold in China’s lucrative media and entertainment markets. This is a story that we have covered here before, but what I found most interesting about this article was the language that it used. It situated MMA as an outgrowth of the traditional Chinese martial arts, and thus their “return” home was something “natural” rather than foreign. Still, it ended the following note: “As the ancestry of modern mixed martial arts, Chinese kung fu enjoys popularity around the world and now it’s time for the time-honored martial art form to evolve by communicating with the world.”

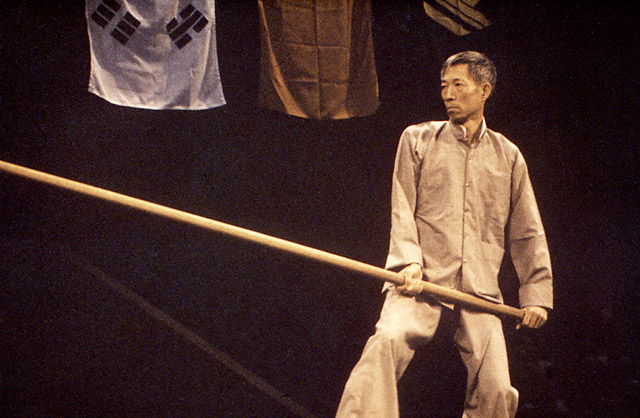

This is not the first time that an MMA promoter has tried to break open the Chinese market and it probably won’t be the last. One of the challenges inherent in getting a foothold is all of the other combat sports that are already popular with Chinese audiences, athletes, media outlets and bureaucrats. By far the most important (and economically lucrative) of these is Sanda. Sascha Matuszak recently wrote a quick introduction to the topic over at Vice’s Fightland blog. It lays out the facts on the ground quite nicely. And while you are there check out his other post on the place of the wooden dummy in modern (post-Ip Man) Chinese martial arts training.

The recent attempt to set a record for the largest taijiquan demonstration, Photo: China News Service / CFP

Where is the calmest place on Earth? According to this photo-essay in the Daily Mail it would have to be in the middle of a massive recently staged (October 18th) Taijiquan demonstration held in Jiaozuo City of Henan province. Some of the photos generated by this event are as breathtaking as one might suppose. But another article in the GB Times does a better job of explaining the purpose of the event. In addition to attempting to set a world record for the largest simultaneous taijiquan practice session, the event organizers were hoping to raise awareness for their bid to have the Chinese martial arts declared an element of “intangible cultural heritage” by UNESCO.

According to a recent study conducted by Yi-Wen Chen, from the University of British Columbia in Vancouver, there may be a number of other reasons for these individuals to continue with their Tajiquan practice. After conducting a review of 33 separate studies (containing about 1,500 research subjects in total) her team found that the regular practice of Taiji can be beneficial for people suffering from a wide range of chronic illnesses ranging from arthritis to cancer. Reuters ran a story (which was distributed by a large number of other outlets) detailing their specific research findings.

National Geographic introduced readers of its blog to approximately “36,000 kids you don’t want to mess with.” The children in question are students of the Shaolin Tagou Kung Fu academy, one of the largest residential wushu schools in China. The occasion for the discussion was an interview with filmmaker Inigo Westmeier who directed the documentary “Dragon Girls.” Recently she collaborated with DB Ben Surkin to turn some of that footage into a music video for Gener8ion featuring M.I.A. The video is great, so if you have not seen it yet be sure to click on the link at the top of the post. The rest of the article is dedicated to a discussion with Westmeier about the production of the documentary, its reception in China and her other projects.

While best known by practicing martial artists as a weapon associated with traditional Karate, the nunchuck exploded into popular consciousness in the west after the 1973 release of Enter the Dragon. More recently a number of law enforcement personal are taking a second look at this simple weapon. This is not the first time that police officers have trained with nunchucks. It seems that their versatility (they can be used to restrain as well as to strike), and their shorter length are winning converts.

While on the subject of nunchucks, the Seattle Times recently ran a piece on the opening of the second installment of the new Bruce Lee exhibit at the Wing Luke museum. The piece includes discussion of Lee’s life in the city as well as some more personal photographs included in the collection. Head on over and check it out.

Chinese Martial Arts in the Entertainment Industry

AMC’s new series “Into the Badlands” (set to debut on Nov. 15) is continuing to pick up a lot of good press. In keeping with what we have already seen much of this focuses on the series’ martial arts content. Evidently the studio believes that this will separate the project both from their other products and competing programs on TV. The New York Daily News ran a longer than expected piece on the upcoming series which you can take a look at here. I thought that it was interesting to note that in the post-apocalyptic future imagined by the show there are no longer any firearms. Obviously that decision gives the directors more freedom to showcase their martial arts assets, and its a common story telling trope in classic Chinese martial arts films (many of which are set in an imaginary past). Still, its not a storytelling device I am very fond of as it ignores the fundamental fact that the Chinese martial arts, as they exist today, are very much the product of a world in which firearms were present.

Qi Shu plays the title role, a young girl who is kidnapped by a nun and trained to become a killer. Source: New York Times.

When it comes to news stories about the Chinese martial arts, director Hou Hsiao-hsien’s recent film The Assassin is breaking the internet. Up to one third of all of the stories that I ran across in the last week were about this film. Readers may recall that the early discussions of this period drama, set in the Tang dynasty, were very positive. Reviewers loved Hou’s visual aesthetic and he won an award at Cannes for his work. Now that the film has actually hit theaters a muck larger batch of reviews are commenting, and unfortunately the results appear to be mixed. While a few reviewers love the film, others are claiming that its falls flat. Most seem to be somewhere in the middle, capable of appreciating the film’s beauty while claiming that it has some notable shortcoming. This review at the Globe and Mail seems to be typical of the current discussion. Everyone seems to agree that what Hou created pushes the boundaries of what you can do with a “normal” martial arts film, but there is less consensus as to whether that was ultimately a good thing.

Of course there is always a lot of classic Kung Fu cinema out there just waiting to be rediscovered by audiences. Consider for instance the 1978 Shaw Brothers film “Heroes of the East” starring Gordon Liu, Yuka Mizuno, Kurata Yasuaki and directed by Liu Chia Liang. It would be an understatement to say that the film as has interesting political subtext, and given current events, it once again seems timely. Check out this post over at Vice Sports which discusses the film as well as its historic and current geopolitical context.

Martial Arts Studies

There have been a number if important developments in the area of Martial Arts Studies. First off, the publisher Rowman & Littlefield (who helped to sponsor our recent conference at the University of Cardiff) have announced the creation of a new book series dedicated to producing titles within the field of Martial Arts Studies. Paul Bowman will be the series editor. In the interest of full disclosure I should state that I am also a member of the project’s editorial board. Obviously this is an important step in developing Martial Arts Studies as it ensures a dedicated outlet for new monographs and will help to build visibility among readers. To find out more about the book series click here.

Paul recently presented a paper titled “Making Martial Arts Studies: A Tale of Two Books.” Follow the link to read a copy of the paper or to watch video of his presentation. Also, researchers interested in publishing in the interdisciplinary journal Martial Arts Studies should check our recent Call for Papers regarding an upcoming special issue titled “The Invention of Martial Arts.”

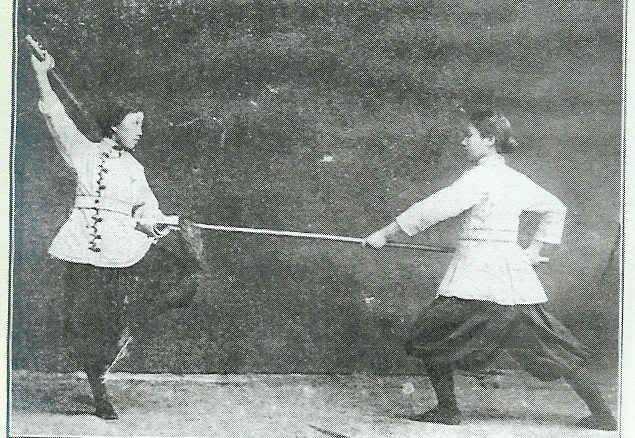

Wendy Rouse, who teaches in the Department of Sociology and Interdisciplinary Studies at San Jose State University, recently uploaded a paper to Academia.edu titled “Jiu-Jitsuing Uncle Sam: The Unmanly Art of Jiu-Jitsu and the Yellow Peril Threat in the Progressive Era United States” (Pacific Historical Review, Vol. 84 No. 4.) This looks like it will be an important article for anyone interested in the early history of the Asian martial arts in the West or those working on questions of masculinity, national identity and racial politics. The abstract is as follows:

The emergence of Japan as a major world power in the early twentieth century generated anxiety over America’s place in the world. Fears of race suicide combined with a fear of the feminizing effects of over-civilization further exacerbated these tensions. Japanese jiu-jitsu came to symbolize these debates. As a physical example of the yellow peril, Japanese martial arts posed a threat to western martial arts of boxing and wrestling. The efficiency and effectiveness of Japanese jiu-jitsu, as introduced to Americans in the early twentieth century, challenged preconceived notions of the superiority of western martial arts and therefore American constructions of race and masculinity. As Theodore Roosevelt and the U.S. nation wrestled with the Japanese and jiu-jitsu, they responded in various ways to this new menace. The jiu-jitsu threat was ultimately subjugated by simultaneously exo- ticizing, feminizing, and appropriating aspects of it in order to reassert the dominance of western martial arts, the white race and American masculinity.

Brill has recently released a new volume titled The Fighting Art of Pencak Silat and its Music: From Southeast Asian Village to Global Movement edited by Uwe U. Paetzold of the Robert Schumann University of Music, Düsseldorf and Paul H. Mason from the University of Sydney. Silat has generated a fairly good sized collection of academic studies in the past and that number seems to have accelerated in recent years. This study appears to be unique in the degree to which it has been shaped by ethnomusicology in addition to other more typical fields including sociology and anthropology. The publisher’s note is as follows:

Fighting arts have their own beauty, internal philosophy, and are connected to cultural worlds in meaningful and important ways. Combining approaches from ethnomusicology, ethnochoreology, performance theory and anthropology, the distinguishing feature of this book is that it highlights the centrality of the pluripotent art form of pencak silat among Southeast Asian arts and its importance to a network of traditional and modern performing arts in Southeast Asia and beyond.

By doing so, important layers of local concepts on performing arts, ethics, society, spirituality, and personal life conduct are de-mystified. With a distinct change in the way we view Southeast Asia, this book provides a wealth of information about a complex of performing arts related to

the so-called ‘world of silat‘.

Unfortunately you will probably need to head to your local university library to find a copy of this book. At $175 a copy I doubt that it will end up on my shelf in the near future. Fortunately Gisa Jähnichen has uploaded a copy of her chapter titled “Gendang Silat: Observations from Stong (Kelantan) and Kuala Penyu (Sabah).” This will be especially interesting for students with a background in music or an interest in performance.

Michael Clarke, a long time karate practitioner and Kyoshi eighth dan, will be releasing an autobiographical work titled Redemption: A Street Fighter’s Path to Peace (Ymaa Publication). While not a scholarly work students of Martial Arts Studies may find this interesting more as a “primary text” due to its extensive discussion of the modern history of Karate and social observations on violence and martial arts. It is due out in March of 2016.

Lastly, be sure to check out the first part of my recent interview at Kung Fu Tai Chi magazine where Jon Nielson and I sit down with Gene Ching to discuss our book on the social history of the southern martial arts, Wing Chun and the importance of recent development in martial arts studies. Expect the second half of this detailed interview to posted sometime next week.

Kung Fu Tea on Facebook

As always there is a lot going on at the Kung Fu Tea Facebook group and this last month has been no exception. We discussed modern Daoist meditation practices, the life of Ma Liang (both a warlord and martial arts reformer) and watched some new interviews with Adam Hsu. Joining the Facebook group is also a great way of keeping up with everything that is happening here at Kung Fu Tea.

If its been a while since your last visit, head on over and see what you have been missing.

![Representatives of Chinese Sanda fighters participate Wednesday's news conference. [Photo provided for chinadaiy.com.cn]](http://chinesemartialstudies.files.wordpress.com/2015/12/sanda-news-conference.jpg?w=750)